As we readied for Day 3 of our pilgrimage, the fate of my Seattle-born Uncle Suetaro became even more haunting. From my study of the Battle of Leyte and from now standing on its very soil, the enormity of doom that hovered unbeknownst over Uncle Suetaro became very clear.

Vastly outnumbered by the Allied invasion forces and out-supplied, only 20 young men out of the 2,550 in his Hiroshima-based 41st Infantry Regiment would ever leave Leyte. The remains of the 2,530 soldiers are still there.

Day 3 – The Morning

The same torch-like sun greeted us once again in the morning as we gathered for Day 3 of our pilgrimage. Today promised to hold the biggest emotional impact of our journey: we will be actually tracing the footsteps of our Uncle Suetaro.

While our young drivers expertly dodged two-cycle motorcycles, pedicabs and colorful small buses with passengers holding on to dear life on the back bumpers, we headed up to the once standing and vital steel bridge at Cavite… and my Uncle’s destiny.¹

Due to high costs, I was unable to use my smartphone’s GPS nor Google maps to track our movements nor mark our coordinates; as such, we came upon the bridge without notice…but we had indeed arrived.

Due to high costs, I was unable to use my smartphone’s GPS nor Google maps to track our movements nor mark our coordinates; as such, we came upon the bridge without notice…but we had indeed arrived.

As we got out of the vans, it firmly struck me that we were in audience of my uncle’s past footsteps… The footsteps of the uncle I never had the chance to meet because of war. Our paths had finally crossed.

In 1944, it was referred to as the Mainit River Bridge; its remnant was right in front of us. We stood on its replacement bridge about 50 yards away, with heavy traffic rushing by, barely passing us on the narrow walkway. The original steel bridge spanned from right to left in the above picture.

A dark weight bore down on me as I stared at the single concrete column. Like on some of the walls and fences at Normandy, it was pot-marked with bullet holes and artillery damage from that day. I could hear the gunfire, the artillery, the whump of mortar rounds hitting their targets and the desperate screams of young men dying. My skin – even in 90F weather and covered with sweat – got goosebumps and my eyes teared up. This is where I believe my uncle met his likely death… on the left side of the river and above centerline in the picture. According to Mr. Ota’s book, my uncle’s lieutenant in charge of the 37mm anti-tank guns, Lt. Shiduoka, was killed; in addition, over 1,000 Japanese soldiers died between October 30th and November 1st.

Although the bridge was rigged with explosive charges but sadly for the Japanese Army, the combat engineer was killed before he could set off them off. The bridge was left intact. On the other hand, it was good for our US Army as essential Sherman tanks and self-propelled howitzers could now traverse the muddy river to engage the enemy. I can “feel” both sides of the battle. Victory and defeat. Perhaps that is a curse.

I offered gassho, the Buddhist way of prayer, to all those young men – especially to Uncle Suetaro – while on that bridge, quivering with the weight of the traffic lumbering over it. Anguish filled my chest as tears filled my eyes.

I wonder how my dad or grandmother would have reacted if they had seen it.

The First Memorial Service

If Uncle Suetaro had survived the combat, we followed the road towards the west (see map above); it was the same road they would have retreated on – albeit dirt or mud the evening of October 30, 1944. We then entered the town of Jaro.

We then turned north towards Carigara Bay but stopped after about a kilometer. (See red arrow in battle map above.) I didn’t know why until we started to get out. We were to conduct our first official memorial service of this pilgrimage at this spot. Believe me that the memorial service in and of itself worried me as I am not Japanese. I am American. Japanese pay attention to minute actions; acting in one way may be harmonious, another way very rude and unacceptable.

And it is true: a Japanese man can come to America and become American… but an American can go and live out the rest of his life in Japan and never become Japanese. Although I was born in Japan, the latter is me.

_____________________________________________

We had stopped on a narrow two lane street, across from a small dwelling filled with a number of children. As we left the coolness of the van, the sweltering heat greeted us once again. Mr. Ota explained that just beyond our view from the road was the low-lying hills on which the 41st Regiment had hidden themselves and fired upon the tanks and Col. Newman on November 1.¹ And he was right: Col. Newman would not have been able to see the low-lying hills, especially since the vegetation would have been much thicker on November 1, 1944 (see photo above). The Japanese Army selected their defensive position well.

Our party assembled their articles to be carried to the memorial service location: photographs, food, cigarette packs, water, incense and osake. Things that a young Japanese soldier longed for out on the battlefield. Mr. Ota’s young, tall son Daichi lugged along a small side table for us in this heat.

My guess is we walked inland about a quarter of a mile from the dwelling. We stopped at the base of the low-lying hill, now clearly visible in front of us.

Palm fronds were swaying in a consistent but warm breeze and ground cover would crackle as we stepped upon them. But in drastic contrast to explosions caused by US 105mm howitzer shells exploding or the sound of Japanese Nambu machine guns blasting away 71 years ago, some birds were joyously singing about us. Perhaps they knew why we were there – for peace and remembrance.

While many tried to shield themselves from the searing sun by standing in the little shade that was available, the folks meticulously placed their offerings and remembrances of family.

There was a first time for everything. This service was going to be definitely mystifying for me. And I could see Mr. Ota went though a lot of trouble so that we would have a memorable service filled with honor, release of grief and closure. He did the planning and preparation on his own; we didn’t have to ask him.

The service would last about 20 minutes. The program entailed:

- Singing of the Japan’s hymm

- A minute of silence

- Sutra chanting by Mr. Kagimoto

- Incense offering and gassho

- Reading of letters

- Singing of the 41st Infantry Regiment regimental song

My very amateurishly shortened and edited video is below, including a portion of Masako reading her poignant yet touching letter to her Uncle Suetaro who, for us, was still somewhere in the low lying hills in front of us.

_______________________________________________

As Masako stared at the framed photo of Uncle Suetaro in his Imperial Japanese Army uniform, taken before he left Japan, she began to tenderly read her letter to him. Masako said in essence:

“Dear Uncle Suetaro, we finally get to meet again. After you were drafted, I remember being taken twice to see you at your army base in Fukuyama. My mother took me the first time; we took you some makizushi which you very discreetly kept out of sight and ate very quickly. Then my father took me to see you the second time. You said to him many times, “Please look after my mother…

You had sent me postcards from your station in the Far East, showing pictures of the local children. They are still forever etched in my heart.

On this land upon which I stand now, Uncle, you fought courageously though you were so very hungry and exhausted.

After the war ended, your oldest brother Yutaka² came back from America and officially adopted me into the Kanemoto family. On February 8, 1954, your mother Kono took her last breath while her head was resting in my arms.

I have raised two children and as if destiny, I have resolutely carried on the family name on your behalf.

Uncle Suetaro, please sleep in peace.”

There wasn’t a dry eye. I think even the birds were crying.

_________________________________________

The second service in Part 5

NOTES:

- On October 30, 1944, both Japanese and American battle records show my uncle’s 41st Infantry Regiment of the Imperial Japanese Army and the US Army’s 34th Infantry met in fierce violence at the bridge, ending in indescribably horrific hand-to-hand fighting to the death. For my story combining both American and Japanese records on this battle, please click here. (Ms. Teraoka’s uncle, Lt. Nakamura, was also engaged in this combat as Communications Officer but survived the battle.)

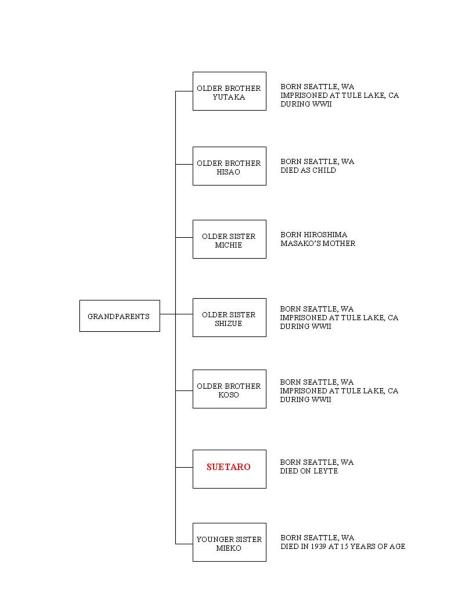

- Uncle Yutaka became the head of the family after the war. He, like my dad Koso and Suetaro’s older sister Shizue, were imprisoned in Tule Lake, CA with their families after the outbreak of war although all were American citizens. For clarification purposes only: