End of a Samurai Son’s Life

After radio chatter in supposed secret Japanese naval code was intercepted by MAGIC on April 13, 1943, the US Navy jumped into action. The US Navy brass now knew of Yamamoto’s projected flight schedule just five days later.

But to fully appreciate this, of course, it is critical to note this was 1943 and during a most vile world war. There was no faxing, texting, internet or the like. Also, Yamamoto’s plane may not start that day, weather may alter the flight or he may just get sick (He did suffer from a form of beriberi.).

But some huge questions that had to be answered in only three days if the shoot-down were to occur successfully:

- Who was going to order/approve the killing?

- How was it going to get carried out? And,

- How can the Japanese be kept from figuring out our secret that we broke their secret code? (1)

______________________________________

Sources differ on who approved the go-ahead for Admiral Yamamoto’s killing.

Some sources say Admiral Nimitz said go.

Some sources say Admiral Nimitz refused to give the order to kill Admiral Yamamoto and deferred the decision to his superior, Admiral King.

Some sources say no military brass wanted to approve the killing and that it ultimately came from FDR (which by definition becomes an assassination). Although no document from that time could be found, several items indicate FDR was at least involved. (1) (2)

But one thing is certain; when Bull Halsey found out the mission was a go, he stated, “TALLY HO X LET’S GET THE BASTARD.”

____________________________________

Some buried history on the actual mission to kill Admiral Yamamoto:

- In a tent choked with humidity on Guadalcanal’s Henderson Field on April 17, 1943, Admiral Marc Mitscher read the message marked ‘TOP SECRET’, signed by the Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox. In attendance was Major John W. Mitchell, USAAF. He would plan and lead the flight:

“SQUADRON 339 P-38 MUST AT ALL COSTS REACH AND DESTROY. PRESIDENT ATTACHES EXTREME IMPORTANCE TO MISSION.” - The recently deployed P-38G Lightning was the only fighter that could accomplish the shoot-down. Other fighters like the US Navy’s Grumman F4F or new Vought F4U Corsair simply could not fly the approximately 800 mile round trip. Even then, without Charles Lindbergh’s engineering insights to lean-burn, the flight may have been impossible for the P-38Gs. Still, the P-38s required external fuel tanks, one of which must be a 330 gallon capacity, the other 150. They were located at Port Moresby, expedited to Guadalcanal then hurriedly attached to the fighters in an all night effort.

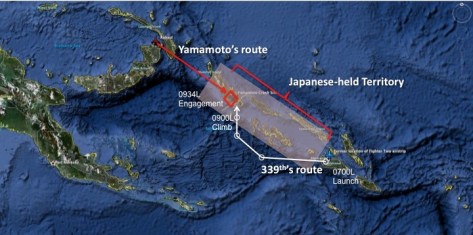

- A Marine named Major John Condon actually drafted up the flight plan first but Major Mitchell rejected it with only 12 hours of so before takeoff. With input from several key pilots, Mitchell rushedly planned out the mission as the shootdown was to occur the next day with the flight leaving early in the morning! Relying on Yamamoto’s trademark punctuality, Mitchell precisely “walked back” the flight path from the expected intercept time over the southwest coast of Bougainville at 9:35 AM.

Source: U. S. Naval Institute.

4. It was determined there would be four “killer” attack planes and 14 escort planes to handle the anticipated six Zero escort fighters and to compensate for aborts. The 14 escort fighters were also in anticipation of the dozens of other land-based Zero fighters that may be airborne. The four killer planes were responsible for the single Betty bomber carrying Admiral Yamamoto. (3)

5. Mitchell, in leading the flight, demanded the standard USAAF compass on his P-38G be replaced by a larger and more accurate Navy compass. “Dead reckoning” would be the order of the day and exact headings were an absolute requirement – therefore, the need for the most accurate compass available. All they would see in their 400 mile flight out would be water.

6. One P-38 suffered a flat tire at takeoff and another’s fuel transfer from belly tanks failed, leaving 12 escort P-38s for the anticipated combat. Surprisingly, these two planes that dropped out due to the mechanical failures were two of the four original killer planes.

7. Per a recent Military Intelligence Service’s veteran’s report, “At 7:25 AM on April 18 1943, the American pilots departed

Henderson Field, Guadalcanal, to travel a circuitous all water route at ten to thirty feet above the water and radio silenced to avoid enemy radar detection. At 8:00 AM, 35 minutes later and 700 miles away, Yamamoto’s convoy took off on schedule from Rabaul airfield and (then) arrived over the southwest coast of Bougainville at 9:35 AM, the exact time the P 38s arrived there.”(2) The flight path avoided all possibility of being seen from occupied islands or radar. Being literally at sea level, it was sweltering in the cockpit. Mitchell had to fight of drowsiness as one mistake meant death an instant later.

8. Miraculously, Mitchell had guided his attack force to within one minute of the targeted arrival time. The third pilot spotted the flight but it included TWO Betty bombers, not the single one dictated in the decoded secret message. At this moment, Mitchell was not sure if this was Yamamoto’s flight. Forunately, Mitchell made the snap decision to attack, said, “Skin them (meaning drop fuel tanks),” and began combat.

9. Lanphier and Barber both had hits on the Betty bomber that carried Admiral Yamamoto. However, Lanphier’s gun camera footage shows his rounds striking the Betty bomber, causing part of the left wing to split off. The bomber then crashed into the jungle.

Here is footage from both American and Japanese viewpoints (scroll to the 5:28 mark). It does show in slow motion Lanphier’s gun camera footage where he shoots off part of the left wing of Yamamoto’s plane. (Important note: the “gunfire” you hear in the actual gun footage is edited in. The gun cameras were silent B&W film.)

10. One killer P-38 piloted by Lt. Raymond K. Hine was lost; he originally began the flight as an escort fighter but moved up when the two killer planes had to abort. There were various sightings from Japanese reports which claim his supercharger was hit and engine smoking when he headed out to sea. He was never heard from or seen again. In spite of claims by the USAAF pilots, not one Zero was shot down although several were damaged.

11. The six Japanese Zero pilots assigned to escort Admiral Yamamoto were:

All were shamed, of course, for failing in their duty to protect Admiral Yamamoto but they were up against tremendous odds. Japanese brass decided not to have them commit suicide; the brass knew they would perish in combat in their hopes Yamamoto’s death woukd be kept underwraps. Sure enough, all but Kenji Yanagiya would be killed in action within a short period. Yanagiya was severely wounded, losing his right hand and was sent home. He passed away in 2008 at the age of 88.

12. Per John Connor, History.net, he writes:

“At every stage, planners had stressed the need for secrecy. But even before the P-38s had landed, security was compromised.

As the returning planes neared Guadalcanal, Lanphier radioed to the control tower: “That son of a bitch will not be dictating any peace terms in the White House.” Lanphier’s announcement was shocking to others on the mission. Air-to-ground messages were broadcast in the clear, and the Japanese monitored American aviation frequencies. Lanphier’s message left little to the imagination. Bystanders on Guadalcanal, including a young navy officer named John F. Kennedy, watched as Lanphier executed a victory roll over the field before landing. “I got him!” Lanphier announced to the crowd after climbing out of his cockpit. “I got that son of a bitch. I got Yamamoto.”

Halsey and Nimitz, when they found out, went nuts as if the Japanese heard the message, they would realize that Lanphier knew Yamamoto was on board which would be impossible unless we broke their JN-25 naval code.

13. Behind the scenes, President Franklin D. Roosevelt reacted with glee, writing a mock letter of condolence to Yamamoto’s widow that circulated around the White House but was never sent:

Dear Widow Yamamoto:

Time is a great leveler and somehow I never expected to see the old boy at the White House anyway. Sorry I can’t attend the funeral because I approve of it.

Hoping he is where we know he ain’t.

Very sincerely yours,

/s/ Franklin D. Roosevelt

14. The US definitely wanted to keep the Japanese Navy from suspecting we had broken their JN-25 code. In a ploy to make it look like Mitchell’s flight was indeed a chance of luck, the USAAF sent out similar patrols on subsequent days. Besides, the Japanese did NOT publicize his death for about two months; as such, the Americans could not possibly know Admiral Yamamoto was killed.

15. Decades later, the feud between Barber and Lanphier continued as to who shot Yamamoto down. At the end, the US Navy officially awarded the “kill” to Barber. When that happened, ironically, Lanphier lost his “ace” status.

16. Per the Japanese Navy’s coroner’s report, Yamamoto was found ejected from the crashed plane but still strapped into the pilot’s seat. Further, that he was still clutching his family’s samurai sword. The report stated that the seat was upright resting against a tree and that his face looked unchanged. It further stated the cause of death was from two .50 caliber rounds, one into his back and another entering though his jaw and exiting above the right eye. (Author’s note: I am highly suspect of this report given it was from propaganda driven wartime Japan. Although I never served, I cannot fathom his face “looking unchanged” when a .50 caliber round exited above his right eye after entering through his jaw. I also cannot believe he was still clutching his samurai sword after being ejected from the plane.)

17. The second Betty bomber carried Yamamoto’s Chief of Staff Vice Admiral Matome Ugaki. He and two other sailors survived the crash into the ocean after being shot down albeit with a broken arm. He would recover from his wounds but would not return from the infamous last kamikaze attack of WWII which he led on August 15, 1945. He did not make his target. He would leave behind his meticulous diary, a wealth of information.

___________________________________

More to follow in Part X.

___________________________________

Footnotes:

(1) It was vital that the Japanese not know their naval codes (the JN-25) had been broken. If they did, they would react and modify their code. This would terminate the US Navy’s ability to track and sink military and most of all, merchant shipping of vital natural resources taken from captured countries. As written in “What Did FDR Know”, the sinking of many tons of merchant vessels was made possible by our breaking their JN-25.

(2) “…The message was decrypted and translated at FRUPAC by Marine Lt Col Alva Byan Lasswell and was passed the next day to

Commander Ed Layton, CINCPAC intelligence officer. Admiral Chester NIMITZ, CINCPAC, sent the message to Washington. President Franklin Roosevelt approved and requested the

shoot down of Admiral Yamamoto’s air convoy be given the highest priority. This was conveyed to RADM Marc A. Mitscher, commander of the Solomons region, via NIMITZ and Admiral Halsey who was responsible for that region.” – “Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto Air Convoy Shoot Down” report, JAVA, April 18, 2014. The author was a noted Military Intelligence Service member during WWII.

(3) The original flight organization was:

Initial Killer Flight:

Capt. Thomas G. Lanphier, Jr.

Lt. Rex T. Barber

Lt. Jim McLanahan (dropped out with flat tire)

Lt. Joe Moore (dropped out with faulty fuel feed)

The remaining pilots were to as reserves and provide air cover against any retaliatory attacks by local Japanese fighters:

Maj. John Mitchell (In command)

Lt. William Smith

Lt. Gordon Whittiker

Lt. Roger Ames

Capt. Louis Kittel

Lt. Lawrence Graebner

Lt. Doug Canning

Lt. Delton Goerke

Lt. Julius Jacobson

Lt. Eldon Stratton

Lt. Albert Long

Lt. Everett Anglin

Lt. Besby F. Holmes (replaced McLanahan)

Lt. Raymond K. Hine (replaced Moore and KIA)

The post-World War II period was no easy time for the American people. At the conclusion of the war, Americans were exhausted. They needed a normal economy; they needed peace; they wanted to get on with their lives. President Harry Truman, in seeking cost-cutting measures, ordered a one-third reduction of the Armed Forces. Between 1945-50, Washington, D. C. was a busy place. War veterans were expeditiously discharged, the War Department became the Department of Defense, the Navy Department was rolled into DoD, the US Army Air Force became the United States Air Force, and the missions and structures of all services were meticulously re-examined. In terms of the naval establishment, about one-third of the Navy’s ships were placed into mothballs; in the Marines, infantry battalions gave up one rifle company —Marine Corps wide, this amounted to a full combat regiment.

The post-World War II period was no easy time for the American people. At the conclusion of the war, Americans were exhausted. They needed a normal economy; they needed peace; they wanted to get on with their lives. President Harry Truman, in seeking cost-cutting measures, ordered a one-third reduction of the Armed Forces. Between 1945-50, Washington, D. C. was a busy place. War veterans were expeditiously discharged, the War Department became the Department of Defense, the Navy Department was rolled into DoD, the US Army Air Force became the United States Air Force, and the missions and structures of all services were meticulously re-examined. In terms of the naval establishment, about one-third of the Navy’s ships were placed into mothballs; in the Marines, infantry battalions gave up one rifle company —Marine Corps wide, this amounted to a full combat regiment. A young Sterling Hayden

A young Sterling Hayden

Then, the American propaganda machine took over. They picked up what Yamamoto supposedly said and changed its meaning even more. Posters sprang up all over the place with purposely and understandably exaggerated caricatures demonizing Yamamoto… but most of all, very much mutating the questioning feelings of Yamamoto. Time Magazine even took part.

Then, the American propaganda machine took over. They picked up what Yamamoto supposedly said and changed its meaning even more. Posters sprang up all over the place with purposely and understandably exaggerated caricatures demonizing Yamamoto… but most of all, very much mutating the questioning feelings of Yamamoto. Time Magazine even took part.

I certainly feel he was likely the one with the most military foresight and highly likely the most well balanced. Yes, he was the enemy and FDR approved his assassination in vengeance for the attack on Pearl Harbor… but I am looking at this broadly.

I certainly feel he was likely the one with the most military foresight and highly likely the most well balanced. Yes, he was the enemy and FDR approved his assassination in vengeance for the attack on Pearl Harbor… but I am looking at this broadly. His first ball and chain was the misguided yet all domineering Japanese Army. Since the Boshin War victory, their newly formed Imperial Army’s self-centered view of themselves had snowballed. In other words, they were full of themselves and Yamamoto was handcuffed militarily and politically from a naval standpoint. They were second fiddle.

His first ball and chain was the misguided yet all domineering Japanese Army. Since the Boshin War victory, their newly formed Imperial Army’s self-centered view of themselves had snowballed. In other words, they were full of themselves and Yamamoto was handcuffed militarily and politically from a naval standpoint. They were second fiddle.