Admiral Yamamoto’s Death

Back during the day, there had been a great brouhaha over the killing of Admiral Yamamoto on April 18, 1943. Two USAAF pilots bickered for decades after the war as to who shot Admiral Yamamoto out of the sky. While most attribute the killing to a pilot named Lt. Rex Barber, others believe Capt. Thomas Lanphier Jr. fired the fatal burst from his Lockheed P-38G Lightning.

We will never truly know.

But some lost history first on what led to Admiral Yamamoto’s killing.

The Most Hated Man in America – Even More Than Hitler

By April 1943, Admiral Yamamoto was the most hated man in America by many accounts – more so than Hitler. Think of it this way. Yamamoto was WWII’s version of today’s Osama bin Laden (or however you wish to spell it) on a hate level.

How did it come to be?

Sure, there are Pearl Harbor parallels with bin Laden; bin Laden masterminded the surprise “dastardly” attack on 9/11 on American civilians. (Dastardly. Sound familiar?) The attackers were maniacal terrorists who definitely knew it would be a one-way trip and it was to appease their god… but they didn’t fly their own planes to attack America.

But in my opinion, that’s where the parallels lack some merit if not wrong in substance. For one, Yamamoto as you learned was AGAINST taking on America as an enemy unlike bin Laden. It would be the end of the Japanese empire and he was right. Secondly, the surprise Pearl Harbor attack was against military targets using their own planes. Thirdly, while the attacking navy pilots could die for their emperor on this mission, it was not their desired outcome. They did not see this for the most part as a one-way trip.

Sure, it is enough to hate Yamamoto on the surface but how did he become by and large the most hated man in America? It was because of… fake news.

Yes, fake news. Things manipulated or taken out of context.

And it started with the Japanese.

________________________________________

Before the strike on Pearl Harbor and with plans generally in place, Admiral Yamamoto wrote to his close friend, Ryoichi Sasakawa:

“Should hostilities once break out between Japan and the United States, it is not enough that we take Guam and the Philippines, nor even Hawaii and San Francisco. To make victory certain, we would have to march into Washington and dictate the terms of peace in the White House. I wonder if our politicians, among whom armchair arguments about war are being glibly bandied about in the name of state politics, have confidence as to the final outcome and are prepared to make the necessary sacrifices. (1)”

Well, a bit after the attack on Pearl, the Japanese propaganda machine went into action. For the most part, folks, the Japanese propaganda/news media would GREATLY exaggerate if not lie to present the rosiest war picture to boost the morale of the citizens. In this case, the contents of Yamamoto’s private letter got “leaked” (sound familiar?) but the militarists dropped his last sentence of what he wrote in its entirely – which therefore shed a whole different tone on what was he truly meant (in bold italics above).

Then, the American propaganda machine took over. They picked up what Yamamoto supposedly said and changed its meaning even more. Posters sprang up all over the place with purposely and understandably exaggerated caricatures demonizing Yamamoto… but most of all, very much mutating the questioning feelings of Yamamoto. Time Magazine even took part.

Then, the American propaganda machine took over. They picked up what Yamamoto supposedly said and changed its meaning even more. Posters sprang up all over the place with purposely and understandably exaggerated caricatures demonizing Yamamoto… but most of all, very much mutating the questioning feelings of Yamamoto. Time Magazine even took part.

Please don’t misunderstand the gist of what I am writing here. These are facts.

___________________________________________

The Killing

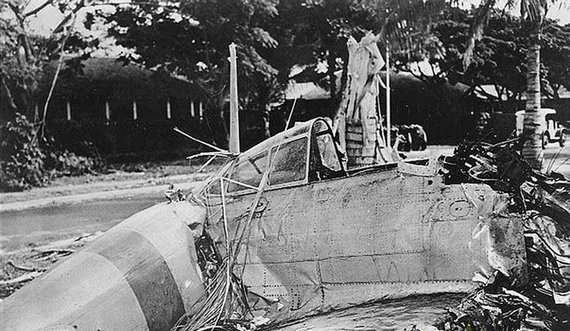

The shoot down of Yamamoto in a moving airborne target 76 years ago was a miracle by today’s standards. Likely, it was mostly luck after the U.S. attack force took off. Today, drones can be sent in with Hellfire missiles with GPS accuracy when a message intercepted.

But in a very primitive way now, that’s how the U.S. killed Yamamoto, the mastermind of the Pearl Harbor sneak attack.

It was Lady Luck.

__________________________________________

In April 1943, Guadalcanal was a dismal place for Japanese soldiers. Through blunders, bad intelligence and exaggerated aerial combat reports, Japanese soldiers had minimal war materials for combat or were simply dying of starvation or illness. It guesstimated that these young boys were trying to fight on less than 1,700 calories a day without such energy staples as rice or potatoes.

Yamamoto was tasked to resupply them by sea but was thwarted by the US Navy and USAAF as we had broken their naval code. They had resorted to using their samurai swords to dig dirt looking for food.

Knowing their dismal state and morale, their consummate leader Yamamoto made the fatal decision to go down to the front lines to boost morale. This would have been akin to Ike visiting the freezing soldiers during the horrendous winter at Bastogne. His initial stop was to have been the naval base Ballale, an active airfield for the Japanese Imperial Navy pilots. His lieutenants strongly urged him not to go but his character gave Yamamoto no other avenue. The plans were made then dispatched by radio.

The Japanese held islands lit up the airwaves with radio chatter on April 13, 1943. The chatter reported their great revered leader Yamamoto was coming down to cheer on the troops. The chatter included his detailed flight schedule as well as he and his second in command Admiral Ugaki would be flying in a Betty bomber escorted by six Japanese Zeroes. Admiral Yamamoto was always punctual – and that would help get him killed.

Well, the radio chatter was in what the Japanese thought was their secret Imperial Japanese Navy Code JN-25D. (3) They believed that “Westerners” could not break it. Well, it was a very closely guarded secret but the US had broken the code by the Battle of Midway. From what I read, the actual JN-25D coded message announcing Yamamoto’s upcoming visit said (translated into English):

“ON APRIL 18 CINC COMBINED FLEET WILL VISIT RXZ,R–, AND RXP IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE FOLLOWING SCHEDULE:

1. DEPART RR AT 0600 IN A MEDIUM ATTACK PLANE ESCORTED BY 6 FIGHTERS. ARRIVE RXZ AT 0800. IMMEDIATELY DEPART FOR R- ON BOARD SUBCHASER (1ST BASE FORCE TO READY ONE BOAT), ARRIVING AT 0840. DEPART R- 0945 ABOARD SAID SUBCHASER, ARRIVING RXZ AT 1030. (FOR TRANSPORTATION PURPOSES, HAVE READY AN ASSAULT BOAT AT R- AND A MOTOR LAUNCH AT RXZ.) 1100 DEPARTRXZ ON BOARD MEDIUM ATTACK PLANE, ARRIVING RXP AT 1110. LUNCH AT 1 BASE FORCE HEADQUARTERS (SENIOR STAFF OFFICER OF AIR FLOTILLA 26 TO BE PRESENT). 1400 DEPART RXP ABOARD MEDIUM ATTACK PLANE; ARRIVE RR AT 1540.“ (2)

(Note: the bolded italics is the portion that pertains to the shootdown. The rest of the decoded message relates to Yamamoto’s schedule AFTER he touches down. US command at Kukum Field decided going for the subchasers would be questionable as the USAAF pilots wouldn’t be able to discern surface ship configurations but they knew aircraft.)

_________________________________

Details of the shootdown, the aftermath and the secrets – from both sides of the Pacific – comes in Part IX.

_________________________________

Footnotes:

(1) “At Dawn We Slept,” (1981) by Gordon W. Prange. Page 11.

(2) – Source: US Naval Institute. Also, the original coded message was in Japanese; it was translated into English by US Army Niseis in the Military Intelligence Service (my Dad’s old unit).

(3) Aiding the effort to completely crack the secret Japanese naval code were two military action events. First, a few days after the US Marines invaded Guadalcanal on August 7, 1942, the Marines capture a complete JN-25C code book.

Then in February 1943, US recovers significant code materials from the I-1 beached off Guadalcanal after a fierce surface battle with two British minesweepers. The captured documents included a superceded JN-25 code book, but no additive book. “As part of the crew at Station AL Guadalcanal, (he) helped rehabilitate the five code books recovered plus many other classified documents and navigational charts. They were sent by courier to Pearl Harbor.” The report continued:

“…The salt-water logged code books retrieved by the Ortolan were taken to Station AL (a small intercept, direction finder, traffic analysis, cryptoanalysis and reporting station on Guadalcanal). There they were dried by being placed on top of a radio receiver to use its heat. The records were kept for about two days to get them in shape for transport. They were taken to the intercept site at Lunga Point, a promontory on the northern coast of Guadalcanal. From there they were sent to CINCPAC’s code breakers at Pearl Harbor.

While the code breakers were trying to exploit the captured code material from the I-1, translators began the task of translating and publishing important documents from the submarine. The U. S. Army Forces in the South Pacific Area (USAFISPA) begins publishing I-1 items in early March. On March 1, the Translation and Interrogation Section, G-2 (my Dad’s unit), of the USAFISPA published a notebook containing entries for January 1-29, 1943. On March 9, the Section published the diary of Seiho Suzuki, 2nd Class Petty Officer, covering the period of early 1942. The same day the Section published the notebook and diary of Masae Suzuki, covering February 11-September 17, 1942. On March 13, it published, extracted from list of communications personnel, the organization of Japanese submarine forces. The next day the Section published communications personnel roster. The Section on March 16, it published a message written on a communication form for encoding and decoding messages. On March 18, it published part of a copy of Naval Regulations (Edition of April 1, 1936, with revisions up to June 30, 1942) and on May 30 published the remainder of the regulations. Also on March 18, the Section published penciled notes, regarding firing torpedoes. On March 21, the Section published bound notes on ciphers and codes. On March 30, the Section published the submarine’s operating log covering the period January 1-28, 1943. The next day it published printed a chart regarding depth charges. The Section on April 1, published a file of messages and notes dealing with the gunnery section, quartering on shore, orders, and dispatches. A printed chart regarding mechanical mines was published on April 7.

In early July 1943 the Section published a notebook, probably belonging to an officer, which appears to have been kept over a period of several years. It provided a list of ships in commission from December 1, 1939 to June 1940. Also published was a code book table, detailed information about equipment on warships, information on submarines, political commentary, information on aircraft, and numerous names of officers and positions. This translation ran 41 pages. The published translations continued. In mid-January 1944, the Section published a Japanese publication on Results and Opinions on Items of Essential Engineering Training and Research in the 6th Fleet for the Year 1941, 7th Submarine Division.

The Intelligence Center, Pacific Ocean Area (ICPOA), was also involved in the exploitation of the I-1 documents. On March 16, 1943, it sent to Washington information regarding hydrographic charts, taken from the I-1, noting “these charts are very accurate reproductions of United States Navy Hydrographic Office confidential charts.”[7] In late March and early April, ICPOA translated and published various documents from the submarine.

All in all, the sinking of the I-1 had been a great success. The documents captured from the submarine provided a wealth of information and intelligence about the Japanese codes and the Japanese navy.” – JN-25 fact sheet, Version 1.1 September 2004 by Geoffrey Sinclair.