Yamamoto’s Barriers to Becoming the Ultimate Admiral

I never served… I never donned on a uniform for this great country.

That in itself qualifies any opinion I may have to offer on World War II military leadership… but from my armchair civilian’s viewpoint, Admiral Yamamoto was one of the elite admirals of World War II.

I certainly feel he was likely the one with the most military foresight and highly likely the most well balanced. Yes, he was the enemy and FDR approved his assassination in vengeance for the attack on Pearl Harbor… but I am looking at this broadly.

I certainly feel he was likely the one with the most military foresight and highly likely the most well balanced. Yes, he was the enemy and FDR approved his assassination in vengeance for the attack on Pearl Harbor… but I am looking at this broadly.

And I also feel he may have become one of the greatest admirals in history if the barriers obstructing him had not existed. Regardless, his military achievements could have been much, much greater had he not been encumbered by conditions smothering him – and yes, he did have one prominent military weakness in my humble opinion.

Factually, he may have succeeded in bringing the US to the peace table if Pearl Harbor was an unqualified success. No, not for “surrender” or to occupy America; that would have been impossible as he knew… but to get America to concede to Japanese expansion in Asia.

His Balls and Chains – Plural

The Uncontrollable Japanese Imperial Army

His first ball and chain was the misguided yet all domineering Japanese Army. Since the Boshin War victory, their newly formed Imperial Army’s self-centered view of themselves had snowballed. In other words, they were full of themselves and Yamamoto was handcuffed militarily and politically from a naval standpoint. They were second fiddle.

His first ball and chain was the misguided yet all domineering Japanese Army. Since the Boshin War victory, their newly formed Imperial Army’s self-centered view of themselves had snowballed. In other words, they were full of themselves and Yamamoto was handcuffed militarily and politically from a naval standpoint. They were second fiddle.

In American terminology, Yamamoto was a “dove” in a way, primarily because he realized Japan relied on imports of oil and steel from America. The Army clearly wanted to invade neighboring Asian countries and take these resources by force.

Yamamoto was also forced into planning the attack on Pearl Harbor because the hawks in the Imperial Army-controlled government signed the Tripartite Pact in September 1940. He knew this would cause Japan to become a clear enemy and anger FDR. As the nail in the coffin, FDR through the League of Nations instituted an embargo on oil and steel. The “hawks” went berserk.

“If I am told to fight regardless of the consequences, I shall run wild for the first six months or a year, but I have utterly no confidence for the second or third year. The Tripartite Pact has been concluded and we cannot help it. Now that the situation has come to this pass, I hope you will endeavor to avoid a Japanese-American war.” – Admiral Yamamoto to Premier Konoye Fumimaro after Japan signed the Tripartite Pact.

Further, the “hotheads” in the Japanese military were so war focused that they lost sight of the fact their own natural resources – being an island country – was dismal. “How could Japan wage a war,” Yamamoto knew; Japan’s natural resources were (1):

Copper 75,000 tons yearly (less than 50% required militarily)

Iron Ore 12% of national requirements

Coking Coal None

Petroleum 10% of needs

Rubber None

In another lesser known angle, the production of military aircraft in any great number was a pressing matter for Japan. In fact, the Imperial Army-controlled leadership simply allocated aircraft production right down the middle: one-half to the Army, one-half to the Navy. Yamamoto was tasked with protecting the entire Japanese empire with his allocation of aircraft while the Army was only focused on land action. This was more ironic in that Yamamoto championed the development of these Zeroes and the Betty bombers, both used by the army.

The “Overly Cautious” Vice-Admiral Nagumo

The second and likely Yamamoto’s heaviest ball and chain – if not the sinker at the end of a fishing line – was Admiral Chuichi Nagumo (南雲忠一). It is my belief that most importantly, the outcome of the attack on Pearl Harbor may have been truly been a death blow to the U.S. if Yamamoto himself had been in command of the attack fleet instead of Nagumo.

Long story short, Nagumo was Commander in Chief, 1st Air Fleet. He was in command of the world’s most deadliest carrier-based naval air strike force in history at that time, bound for Pearl Harbor.

However, he was raised a ship-based torpedo man and was well versed in surface maneuvering. He had only had commands of destroyers, cruisers and a battleship before being appointed to this position of commanding the most powerful carrier based air strike force. Even a fellow admiral (Tsukahara) opined that essentially Nagumo had zero experience in the capabilities and potential of offensive naval aviation let alone in battle.

By the way, Nagumo and Yamamoto were like oil and vinegar. In fact, while Yamamoto’s attack plan for Pearl was extremely well planned out, Nagumo had little faith in it and argued against it.

So how did he become in charge of Yamamoto’s six carrier Pearl Harbor attack force if he wasn’t qualified and did not support the attack plan orchestrated by Yamamoto?

It was because of… his seniority. Simple as that.

You see, in those days and even today, Japan is entrenched in “etiquette” and social ladders. Nagumo had the most seniority among admiral-rank officers and therefore was “rightfully” given the “honor” to command. Not even Yamamoto could change that. (Accepting Nagumo would be fleet commander, Yamamoto ensured his two most highly regarded lieutenants were assigned to surround Nagumo during the Pearl Harbor attack – Minoru Genda and Mitsuo Fuchida.)

But most of all, Nagumo was overly cautious. Timid may be another word to describe what I see forthwith:

- In spite of heeding Genda and Fuchida’s strong urging to send a third wave at Pearl Harbor, he assessed the situation conservatively. He ordered the planes and ordnance below and turned the fleet around after only two waves. His apparent reasoning was to not lose a carrier to air attack from the Americans while Yamamoto was prepared for two carriers lost. Nagumo made this decision in spite of Fuchida circling above Pearl in the clouds for about two hours during the attack, professionally observing the damage at Pearl and providing a detailed accurate report in person to Nagumo. The purpose of the third wave to was destroy repair and fuel facilities. By destroying such assets, the U.S. would NOT have as quickly re-floated/repaired the badly damaged ships. However. to be fair, this is not to say that if Nagumo had sent the third wave that the mission would have been accomplished.

While Japanese propaganda blatantly lied to the public that the American fleet had been completely destroyed by Nagumo, that was far from the truth. While Yamamoto had heard smatterings of what really happened on board the Akagi (Nagumo’s flagship), Fuchida flew in ahead of the fleet and personally gave Yamamoto a detailed report of the situation and how Nagumo’s timidity resulted in an incomplete mission. The whole PURPOSE of the secret attack was to totally cripple the U.S. fleet including fuel and repair docks. Yamamoto concluded the Nagumo-led attack failed to complete its mission. Because the propaganda had made Nagumo into a national hero, Yamamoto could not do much. In typical Japanese fashion, i.e., a veiled insult, he didn’t congratulate Nagumo when they met. Instead, he told Nagumo to ready himself for another battle. Think about it. In essence, if Nagumo had completed his mission, there would be no further battle. Yamamoto was furious but did not show it. - The next ultimate Nagumo failure was at the Battle of Midway. Again, he was in command of a four carrier strike force which outnumbered the American fleet of three carriers.(2) In support of Nagumo, however, the Americans had cracked the Japanese naval code, knew of the impending attack and had taken an immense gamble to set up an ambush at sea. During the battle, Nagumo’s overly cautious nature resulted in delays in launching another strike against Midway.(3) The carrier decks were loaded with bombs, torpedoes and fuel when attacked by dive bombers from the Enterprise (on which Mr. Johnson was again manning anti-aircraft guns). Within minutes, two Japanese carriers were sunk. Nagumo would lose the last two in short order while the U.S. lost the Yorktown.

Per his quote above, Admiral Yamamoto had forecast that his navy may rule the Pacific for six months to perhaps a year without a successful preemptive strike to eliminate the US naval fleet at the get-go. He was right. The Battle of Midway was six months after Pearl Harbor… and the preemptive strike had failed. - Two months after Midway, August 1942, there was an intense sea battle, the Battle of the Eastern Solomon Islands near Guadalcanal. The U.S. had only two carriers in the area (Enterprise and Saratoga under Admiral Fletcher) while Nagumo, who was again in command, had SIX. Yamamoto’s orders to Nagumo were for his 3rd Fleet to seek out and destroy the American carrier force. In spite of the numerical superiority, Nagumo lost the carrier Ryujo but damaged the Enterprise severely. (My neighbor, Mr. Johnson USMC, was a US Marine serving on board the Enterprise manning 20mm anti-aircraft guns and was wounded. See his story here.) While both Nagumo and Fletcher didn’t have the bellies to engage the other and fight, Yamamoto was furious that Nagumo once again failed to successfully engage the two carriers and sink them due to indecisiveness and from being overly cautious.

Yamamoto’s Major Flaw

From early in his career, Yamamoto’s vision for a future offensive carrier based navy showed tremendous insight and intelligence. His rise up the ranks allowed him to achieve his goals in steps. Train the best aviators, develop advanced specialized attack aircraft, cease building battleships and build world-class carriers and institute intensive training and safety regimens. He was also an excellent planner and a man faultlessly devoted to the Emperor and the Japanese empire.

But one aspect of naval warfare he was unable to get his arms around involved his submarines. The subs were innovative and fired the tremendously effective and reliable Type 95 and Type 93 “Long Lance” torpedoes. One, the I-400, was the largest sub ever built.

However, Yamamoto did not veer from his belief that his submarines (of which there were not many) were primarily to be deployed against capital ships, i.e, destroyers, cruisers, battleships and hopefully carriers. While the submarines did sink the USS Wasp and fired the final blow to finish off the Yorktown, their successes were not many, thankfully, due to defensive measures taken by the U.S. Navy.

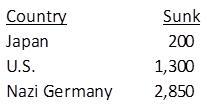

But within this belief, he failed to deploy them effectively against merchant shipping and supply ships. In tabular form, the table below reports the number of merchant ship sinkings by submarines (rounded):

While Nagumo failed to complete the mission to completely destroy the naval assets and facilities at Pearl Harbor, Yamamoto himself contributed to allowing the US to rebuild its Pacific Fleet quickly through his short-sighted and defective deployment of his lethal submarines. While many subs of various classes were deployed about the Hawaiian islands (4), they were generally recalled by January; they were only able to sink a couple of merchant ships and were plagued by mishaps and strong anti-submarine warfare tactics by the US Navy.

______________________________________

The death of Admiral Yamamoto in Part VIII to follow.

______________________________________

Footnotes:

(1) “Yamamoto” by Edwin P. Hoyt.

(2) The four Japanese carriers that were sunk, the Akagi, Kaga, Soryu and Hiryu, were four of the six carrier fleet that attacked Pearl Harbor. This sweetened the victory for the U.S. Japan would NEVER recover from this loss.

(3) To the defense of Nagumo, true military historians cite that Nagumo may have been following Japanese naval doctrine in that it required launch of strike aircraft in full force rather than in piecemeal. Further, that Spruance had already given orders to launch his aircraft so Nagumo’s cautious approach to delay launch would not have made much difference.

(4) Another tip-off to an imminent attack were the number of radio transmissions from Japanese submarine headquarters to it sub fleet off the shores of Hawaii. Per “The Japanese Submarine Force and World War II” by Carl Boyd in 1995: “Part of the reason for the failure of the I-boats in Hawaiian waters concerned the manner of directing operations from afar. The commander of the Sixth Fleet, Vice Adm. Mitsumi Shimizu at Kwajalein, filled the air each night shortly before the air strike with radio messages to his submarines around the Hawaiian islands. A U. S. Navy intelligence officer, then stationed at Pearl Harbor, wrote 25 years later that “port authorities in Hawaii were thus made conscious of the magnitude and to some extent the location of the Japanese submarine menace. They were consequently cautious in routing ships, and this had some bearing on the Japanese lack of success.”

Admiral Nagumo, probably more than any other, realized that he was out of his depth in command of the carrier group. Now then, given his natural trepidation and knowing that Yamamoto had surrounded him with spies, I have little doubt that the man was “cautious” … who would foolishly go where angels fear to tread? Admiral Nagumo was not the only naval officer assigned to command carrier battle groups who lacked practical experience with naval aviation. Admiral Raymond Spruance shared Nagumo’s background. He too was “cautious” (albeit, very cool under pressure) … particularly since the US also had a limited number of attack carriers at their disposal. Who among the short list of very senior naval officers wanted history to remember them as the one who lost their country’s carrier fleet? In any case, as you so capably pointed out, the difference between Spruance and Nagumo is that Spruance was reading Japanese mail; Nagumo was operating in the dark; he was substantially handicapped at a most critical moment in time. Personally, I well-understand his dilemma. A man doesn’t know what he doesn’t know. He must have had a niggle in the back of his mind, however, because as history tells us, he was hesitant and there was (in fact) a good reason for this.

Did the Japanese have a submarine force commander-in-chief? If this responsibility fell on Yamamoto alone, then I can well understand his not being able to get his arms around the submarine force. The Americans did have a submarine force commander and yet, despite this, the US lost 60 submarines in World War II … and somewhere around 3,200 submariners. These submarines and crews as still listed as “on patrol.”

I am enjoying your posts, Koji-san. Keep up the EXCELLENT work.

Thank you once again, Colonel, for your valuable and professional obervations. I understand your line of thought on Nagumo, the fears of being labeled the admiral who lost the carriers and how one would command while in the dark, so to speak.

Yes, Spruance was similar to Nagumo in that he was a cruiser man. However, I understand what would make this parallel somewhat tangential is that Halsey – due to his illness which I last read was a severe case of shingles – recommended Spruance to lead the force in his stead. Yamamoto had no choice with Nagumo. In addition, Spruance had, I believe a captain named Browning (?) as his advisor who did have carrier experience. Unlike Nagumo, Spruance was willing to pull the gun out of its holster and fire… in my humble opinion.

Thank you for continuing my education, Mustang.

I forgot to address your question but in my limited research for this series, all I know is that Shimizu was in charge of the subforce but Yamamoto was CIC. You also know there were many fatalities amongst all submariners and the Japanese were no exception due to the thinner hulls (couldn’t dive as deep nor withstand depth charges). Mishaps also took a toll. Forgive my failing memory but one I-series sub sunk at or near Truk (?) as they were purposely flooding the rear tanks to change the angle but forgot the hatch was open. It sank with many hands on board.

Interesting as always, Koji. I know I will be pondering over this information as I usually do after reading one of your posts. I must also thank Mustang for his added information.

A page from WWII history

https://johnkellynightfighterpilot.wordpress.com/2019/06/01/august-1942/

One of my many blogs. I could not resist.

Hindsight, I think, on 3rd strike. Even Fuchida commented on how much more AAA the 2nd strike ran into than the first. They might have done some damage, but would have lost many planes/pilots, the former being, tho unknown at the time, being exceptionally easy to bring down. I also think Nagumo’s fear of the location of the US carriers was well-founded. We know not that the couldn’t find Kido Butai, but Nagumo didn’t know that then. Had he hung around long enough to launch and recover a 3rd strike, his fear of a counter-attack was well founded.

As to Midway, it was mostly bad luck. His unexpected discovery of the US fleet rightly gave him pause (obviously he had no idea the US was reading JN-25 — my dad was one of them that was). The pause could very well have worked out in his favor had the US strike arrived 20-30 minutes later, or at least more favorably than it did. So many things clear to us now, were not to him at the time.

I hear you, sir, on third strike as I tried to voice about uncertainties. Even if the third strike pilots arrived on target, some may think, “Hell with the fuel dumps. I see a battleship!” From what I read on Japanese websites focusing on Yamamoto, they say he was livid Nagumo did not heed Genda’s and Fuchida’s advice (while Spruance heeded Browning’s,, I believe). You also know from your expertise that Yamamoto had factored in losing two carriers as well as pilots and aircraft; but it appears Yamamoto was extremely upset Nagumo did not command and launch the third wave been given his clear orders before leaving Japan. As Yamamoto said to Nagumo after his return, “Prepare for the next battle.”

Couldn’t have been too mad at him as he remained in command. Today we take for granted that Japan pulled off the PH attack, but at the time it was considered pretty amazing, and I can’t fault Nagumo for not wanting to press his luck.

Yamamoto – even as revered as he was – could not remove or demote Nagumo by ordering it. His placement was under the authority – for the lack of a better English translation – the “personnel office” of the navy. That’s the way it was. However, through indirect finagling, Yamamoto went about strongly in the Japanese way to communicate facts to the office. In November 1942, Yamamoto got his wishes granted. Nagumo was demoted then put out to pasture – he was removed from operational command and put in charge of the Sasebo Naval Base. For Nagumo, it was a severe disgrace.

Hello Mustang. I just recently stumbled across your blog. I am sorry to hear of the suffering the war caused your family on both sides. I will be spending more time reading other things you have covered.j

Thank you for stopping by, Sir… but no need to feel sorry. The entire world felt the pains of WWII. Young men end up dying because selfish politicians with their agendas end up making decisions causing war.

Hello again Koji. I am still wandering around your blog and I am amazed at the depth of information that you have included. I am also amazed that you can write with no sign of the animosity that I would have if our positions were reversed.

I was in the US Navy in the late 50’s and visited both Yokosuko and Sasebo. I did not make any attempt to visit Hiroshima as we were advised not to go there.

I would like to suggest another chapter for your blog since I and many others appreciate your style of writing and I believe that you could provide the coverage that I think it deserves.

The topic is the treatment of the Japanese living in Peru near the end of the war. These people, were forced by the US and Peruvian governments to leave Peru and were detained in camps in the USA.

Here is a book telling the story of one family that was forcibly moved to the US.

Adios to Tears is the very personal story of Seiichi Higashide (1909–97), whose life in three countries was shaped by a bizarre and little-known episode in the history of World War II. Born in Hokkaido, Higashide emigrated to Peru in 1931. By the late 1930s he was a shopkeeper and community leader in the provincial town of Ica, but following the outbreak of World War II, he―along with other Latin American Japanese―was seized by police and forcibly deported to the United States. He was interned behind barbed wire at the Immigration and Naturalization Service facility in Crystal City, Texas, for more than two years.

After his release, Higashide elected to stay in the U.S. and eventually became a citizen. For years, he was a leader in the effort to obtain redress from the American government for the violation of the human rights of the Peruvian Japanese internees.

Higashide’s moving memoir was translated from Japanese into English and Spanish through the efforts of his eight children, and was first published in 1993. This second edition includes a new Foreword by C. Harvey Gardiner, professor emeritus of history at Southern Illinois University and author of Pawns in a Triangle of Hate: The Peruvian Japanese and the United States; a new Epilogue by Julie Small, cochair of Campaign for Justice–Redress Now for Japanese Latin Americans; and a new Preface by Elsa H. Kudo, eldest daughter of Seiichi Higashide.

I worked at Honeywell in Illinois with Seiichi’s oldest son Carlos for a number of years and was not aware of the trials of his early childhood until I read his father’s book.

He, like you, did not appear to hold any animosity for the treatment his family received from the US.

I hope that you can find the time to tell this story since it has never received the coverage in the media that the treatment of the Japanese living on the west coast of the US has received.

sincerely, John Dolan

Thank you again, sir, for the compliment and the background on the story of Japanese living in Peru… and your service to our country.

I am aware of the captivity but only on the surface. It does appear to be similar to that of the US; I do know that FDR was behind that targeting as well, down to negotiating an agreement with Peru to track and deport in exchange for military goods and the like. Crystal City was where Isseis and Niseis deemed to be “more suspicious” were imprisoned – some not released for some time after war’s end. None were found guilty of any crime. I shall consider your wishes, Sir, and thank you once again.