Although my Aunt Shiz passed away ten days before my son and I were to travel to her childhood home in Hiroshima, I believe it was her caring soul that made our journey eerily complete.

Time for heebie-jeebies.

______________________

Like all but one of the siblings, Aunt Shiz was born in Seattle in 1916. My grandparents operated a barbershop as mentioned in “Masako and Spam Musubi“, the first story in this blog. In the picture below likely taken early in 1918, she is standing in front of her mother Kono at their barbershop in Hotel Fujii near King and Maynard in downtown Seattle. Grandma Kono is smiling while looking on; she appears to be holding a straight razor. My relatives tell me Grandma was great with the customers and gave excellent shaves. (If it is a straight edge razor, she’s holding it in her left hand. We have a number of lefties in our family. Hmmm.) Notice the wooden sidewalk:

In this photo taken about five or six years later, the wooden sidewalk has been replaced with concrete. Aunt Shiz shows her friendly character while dancing on the left. You can make out “Fujii” on the sign hanging overhead in the background:

Masako tells me Aunt Shiz was the village “hottie” as she grew up back in those days. It made us laugh but it was true. Surely, she broke a lot of the young boys’ hearts in the village.

She returned to Seattle on April 7, 1935, a vibrant young lady. Amazingly (well, really not), her granddaughter looks very much like her at that age. Genes.

She married and had three boys and one girl. All but one were imprisoned during World War II. They had the dehumanizing horror of having to first stay in vacated horse stalls at the Santa Anita Racetrack in Los Angeles before being transported under armed guard in blacked out trains to Manzanar where they stayed until war’s end. They were American citizens. Incredible, isn’t it?

_______________________

Aunt Shiz, who was my dad’s older sister and last lving sibling, was a true “Kanemoto” as the saying goes. They were much alike…especially when they talked in their “Hiroshima dialect”. Funny they aren’t able to remember when their birthdays are but they sure remember their happy days as children in that Hiroshima home. Both loved to eat. And eat they did. Most of all, they loved sweets. Don’t ask why.

When I see Dad now, I always take him Japanese treats – mainly “manjyu” and “youkan”.

Last October, shortly after her 95th birthday, I took Dad to visit with Aunt Shiz. It is a long drive to and from. While Dad had great difficulty remembering why he was in my car – not just once but several times – there was no hesitation by either of them when they first got a glimpse of each other at Aunt Shiz’s senior home:

Yes, I took a bag of yokan. Its on the front right in the video in a cellophane bag. There were three different flavors, too. They ate them ALL. Really.

But they couldn’t remember who was older. Absolutely precious to our family.

At her funeral service in Los Angeles, her grandson described her perfectly as a very warm person. She loved to hug and give her young relatives a peck on the cheek. That was Aunt Shiz.

_____________________

But back to the story… Some heebie-jeebie stuff. You know… Stuff that gives you a year’s supply of chicken skin.

Our journey to Hiroshima was planned for months. My decision to do so was made after I met with Masako and the others in Hawaii in May and returned home…or so I thought I made that decision. It was as if something took over my thoughts and actions. It was kharma. I was also going to take my oldest son Takeshi (24 years old – very important. Remember that.) who had NEVER been out of the country.

As the time neared, our Hiroshima family was excited my son and I were going. Although those of us here in the States were unaware, in the extreme heat and humidity of Japan, my cousin Toshiro went deep into a 100 year old wooden shed which still exists in a last ditch effort to uncover past family information. He found it…about a thousand pictures from the late 1800’s through shortly after war’s end. That is where the photos of Aunt Shiz and the barbershop emerged from although all were damaged by mildew and insects. They were extremely elated and flabbergasted to have found these vintage family treasures still existing. They began to go through them in the main family room where their “butsudan”, or family altar was. The altar is also about a hundred years old.

A few days after they looked over the treasure, Aunt Shiz passed away quietly… She had fallen asleep in her wheelchair like she frequently did but this time, just didn’t wake up. Oddly, her daughter and my cousin Bessie, who diligently and energetically cared for her for many years, said “…she said she wasn’t that hungry that evening then just passed away”. Not having an appetitite is NOT Kanemoto. I will have to remember that.

_____________________

Bessie immediately notified the family in Hiroshima at which time Masako immediately said, “I saw Shiz in the room while we were looking at the pictures. She passed through the house.” We all got chicken skin when we heard that. Masako does not make things up and is as sharp as a tack at 78 years of age. She has all her wits about her. (That last trait is NOT typical Kanemoto, by the way.) We don’t doubt her.

Bessie suddenly requested I take some of her ashes back with me to the family home for interment. I was honored.

After my son and I arrived at the family home with Aunt Shiz, my cousin Toshiro immediately placed her ashes on the 100 year old altar…in the same room where Masako saw Aunt Shiz. Again, Masako said to us she saw Aunt Shiz in that room before she passed through the house. Creepies.

Shortly thereafter, my Hiroshima family surprised my son and I with the many, many vintage photos. Then to add to the heebie-jeebies, Toshiro remarked, “We know Masako saw Aunt Shiz’s spirit in this room shortly before she died while we were looking over our ancestors’ pictures. Aunt Shiz could have passed away two months ago or next year. But she knew you were coming and in her soul, she wanted to come home now with you. She arranged for all this to happen at this time. She is happy now.”

Wow. I felt like if a day’s worth of chicken skin out of Foster Farms was thrown on my arms. Really creepie-crawly.

_________________________

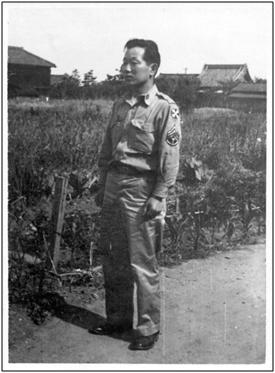

Not over yet… We had her official interment into the family crypt a few days later. My other cousin Kiyoshi – another kind hearted person and the man who invented the first EDM device – came with us to the family burial plot, or “ohaka”. The stone ohaka holds the ashes of my grandparents and their deceased children – including my Uncle Suetaro who was killed on Leyte in the Philippines during World War II as a soldier of the Japanese Imperial Army.

As my son was cleaning the ohaka prior to the interment, Kiyoshi said to my son and I, “Suetaro was 24 years old when he was killed. Now, your son is meeting Suetaro for the first time. Your son is 24 years old. It was all planned for by Aunt Shiz. She picked this time to come home and for Takeshi to be here and to meet Suetaro. It was meant to be this way. To help strengthen our ancestral family bonds although an ocean separates us.”

_________________________

He was right. Masako and Toshiro are right. Aunt Shiz picked this time to come home. She knew we were going. She decided Takeshi was to come. She made everything happen as they did. My son was very moved and affected by this coming together of family…so much so he cried at our farewell dinner.

Do I believe in spirits and kharma?

Yes.