Leyte – November 1, 1944

When we left Part 4, at least one of Uncle Suetaro’s officers – 1st Lt. Shioduka – was killed during this battle per Mr. Ota’s book. If so – and if Uncle Suetaro himself survived – he would possibly left in charge of his 37mm anti-tank gun platoon being a Master Sergeant.

After retreating, Mr. Ota understands that around 2:20 pm, the surviving troops of the 41st Regiment tried to dig in along the banks of the Ginagon River and wait for the US troops to advance into their sights. However, after doing so, a deluge flooded the river and they were forced to move. Nevertheless, defensive positions were established just north of Jaro.

Per Cannon’s Leyte: Return to the Philippines:

At 8 am on 30 October, Colonel Newman ordered the 3d Battalion of the 34th Infantry to start for Carigara down the highway. As the battalion left the outskirts of Jaro, with Company L in the lead, it came under fire from Japanese who were dug in under shacks along the road. Upon a call from the commanding officer of Company L, the tanks came up in a column, fired under the shacks, and then retired. The leading platoon was drawn back so that artillery fire might be placed on the Japanese, but the enemy could not be located precisely enough to use the artillery. Colonel Newman then ordered a cautious movement forward without artillery support, a squad placed on each side of the road and two tanks in the center. The squads had advanced only fifty yards when Japanese fire again pinned them down.

When Colonel Newman came forward and discovered why the advance was held up he declared, “I’ll get the men going okay.” Upon hearing that the regimental commander was to lead them, the men started to move forward. The Japanese at once opened fire with artillery and mortars, and Colonel Newman was hit in the stomach. Although badly wounded he tried to devise some means of clearing the situation. After sending a runner back with orders to have Colonel Postlethwait fire on the Japanese position, he said, “Leave me here and get mortar fire on that enemy position.” As soon as possible Colonel Newman was put on a poncho and dragged back to safety.¹

At this point in battle, Mr. Ota reports, a M4 Sherman was proceeding up the left side of the highway when it came under fire. As the gunner was in the process of reloading (i.e., the breech was open), a 37mm anti-tank round directly entered the M4 Sherman’s 75mm barrel, passed through and carried through the radio before detonating. While all three tank crew members were wounded, the results would have been more disastrous if a round was chambered. Uncle Suetaro manned 37mm anti-tank guns.

Around Jaro and Tunga, fierce and intense see-saw battles took place. Continuing on with Leyte: Return to the Philippines, it reports:

Company E pushed down the left side of the road but was halted by fire from an enemy pillbox on a knoll. A self-propelled 105-mm. howitzer was brought up, and fire from this weapon completely disorganized the Japanese and forced them to desert their position. When the howitzer had exhausted its ammunition, another was brought up to replace it. By this time, however, the enemy’s artillery was registering on the spot and the second was disabled before it could fire a shot.

Elements of the 41st Infantry Regiment, protected by artillery, gathered in front of Company E and emplaced machine guns in a position from which they could enfilade the company. Thereupon Company E committed its reserve platoon to its left flank but shortly afterward received orders to protect the disabled howitzer and dig in for the night. A tank was sent up to cover the establishment of the night perimeter. Company G received orders to fall back and dig in for the night, and upon its withdrawal the Japanese concentrated their fire on Company E. Although badly shaken, Company E held on and protected (a damaged) howitzer…. Company E then disengaged and fell back through Company F, as Company G had done.

Under the protective cover of night, the 41st Infantry Regiment retreated.

Uncle Suetaro’s 41st Regiment, along with troops that had landed at Ormoc during the naval Battle of Leyte Gulf, had succeeded for the moment to stall the advance of the US 34th Infantry. But fighting would continue.

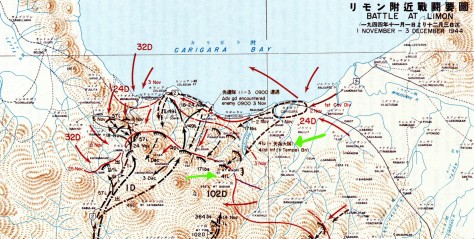

On November 1, General Suzuki determined defending Carigara was untenable. As such, and during the night following, General Suzuki withdrew his troops from Carigara. He ordered his remaining troops – now low on food, ammunition, overwhelmed with dying wounded and no hope for adequate re-supply – to establish strong defensive positions in the mountains southwest of the town in the vicinity of Limon. By “clever deception as to his strength and intentions,” the enemy completely deluded the Americans into believing that his major force was still in Carigara per the Sixth Army’s Operations Report, Leyte.

Of significant note, a massive typhoon hit the Philippines on November 8, 1944. Trees were felled and the slow pace of resupply nearly ceased. Trails were washed away with flooding at the lower elevations. This affected both the IJA and US forces, likely the Japanese the hardest.

I wonder what Uncle Suetaro was feeling as the intense rain from the typhoon pummeled him in the jungle while being surrounded by the US Army. He could not light a fire even if it were safe to do so. I wonder how cold he was or if he was shivering while laying in the thick mud. I wonder what he was eating just to stay alive let alone fight for his life.

Breakneck Ridge: Second Phase

Per Leyte: Return to the Philippines, the 41st Regiment is documented again:

On 9 November the Japanese 26th Division arrived at Ormoc in three large transports with a destroyer escort. The troops landed without their equipment and ammunition, since aircraft from the Fifth Air Force bombed the convoy and forced it to depart before the unloading was completed. During the convoy’s return, some of the Japanese vessels were destroyed by the American aircraft.

The arrival of these (Japanese) troops was in accord with a plan embodied in the order which had been taken from the dead Japanese officer on the previous day.² This plan envisaged a grand offensive which was to start in the middle of November. The 41st Infantry Regiment of the 30th Division and the 169th and 171st Independent Infantry Battalions of the 102d Division were to secure a line that ran from a hill 3,500 yards northwest of Jaro to a point just south of Pinamopoan and protect the movement of the 1st Division to this line. With the arrival of the 1st Division on this defensive line, a coordinated attack was to be launched–the 1st Division seizing the Carigara area and the 41st Infantry Regiment and the 26th Division attacking the Mt. Mamban area about ten miles southeast of Limon. The way would then be open for a drive into Leyte Valley.

Battle Against the US 12th Cavalry Regiment

Per a US 1st Cavalry Division website (http://www.first-team.us/tableaux/chapt_02/) and with the research performed by Mr. Ota, the 41st Regiment was positively identified as being present on “Hill 2348” and fighting against the US 12th Cavalry Regiment (a subset of the 1st Cavalry Division) :

On 20 November, the rest of the 12th Cavalry became heavily engaged around Mt. Cabungaan, about three miles south of Hill 2348. The enemy had dug in on the reverse side of sharp slopes. Individual troopers were again faced with the task of searching out and destroying positions in the fog. Throughout the night of 21 – 22 November the 271st Field Artillery kept the Japanese on the northwest side of Mt. Catabaran awake by heavy concentrations of fire. Before the day was over, patrols from the 12th Cavalry had established observation posts within 150 yards of Cananga on Highway 2 in the Ormoc Valley.

Mr. Ota uncovered a 12th Cavalry report on microfiche in a Japanese governmental archive, dated November 26, 1944. It states in part, “Dog tags from Hill 2348 confirmed elements of the 41st Regiment there.”² In it, it states fog and the muddy terrain made for extreme conditions but they used 81mm mortars to eliminate Japanese positions.

The website continues:

On 26 November, both the 12th and 112th Cavalry Regiments launched attacks against their immediate opposition. The enemy positions that had given heavy resistance to the 112th Cavalry on the two previous days were seized in the afternoon after a pulverizing barrage from the 82nd and 99th Field Artillery Battalions. On 28 November the 2nd Squadron, 12th Cavalry launched another successful attack on Hill 2348 which took the form of a double envelopment. The 1st Squadron renewed their attack on positions on Mt. Cabungaan but sharp ridges held up their advance, The 112th Cavalry continued to move toward its objective…

On 01 December the 112th Cavalry engaged the enemy at the ridge south of Limon. On the night of 02 December, the battle for Hill 2348 reached its climax. The 2nd Squadron, 12th Cavalry suffered heavy casualties from the heavy machine gun fire, mortars, and waves of Japanese troops in suicidal attacks. On 04 December, the 2nd Squadron, 12th Cavalry attacked and overcame a position to its front with the enemy fleeing in the confusion. “A” Troop, of the 112th, in a drive to the northwest, made contact with the left flank elements of the 32nd Division. Thus the drive became an unremitting continuous line against the Japanese and enemy elements that were caught behind the line were trapped.

Throughout 07 and 08 December, patrols of the 5th and 12 Cavalry continued mop up operations. The 1st Squadron, 112th Cavalry moved out to locate and cut supply lines of the enemy who were still holding up the advance of the 2nd Squadron. On 09 December, heavy rains brought tactical operations to a near standstill and limited activity to patrol missions…

…The Division continued the attack west toward the coast over swamps against scattered resistance. By 29 December the 7th Cavalry had reached the Visayan Sea and initiated action to take the coastal barrio of Villaba. On 31 December after four “Banzai” attacks, each preceded by bugle calls, the small barrio fell.

Attempts to Leave Leyte

By January 1945, Japanese command was in shambles. However, some planned effort was made by the IJA to retreat (evacuate) to other islands. Certain departure points were selected south of Villaba, east of the island of Cebu.

The Japanese only had 40 seaworthy landing craft available to evacuate survivors. (A record exists which estimated 268 soldiers of the 41st Regiment were left out of the 2,550 that landed at Ormoc on October 26, 1944.) The US ruled the seas and the skies making any large scale evacuation impossible.

The Reports of General MacArthur states only about 200 soldiers were able to board the landing crafts; however, only 35 made it to Cebu. Once MacArthur figured out this was an evacuation attempt, the Villaba coastline came under intense attack. Evacuation hopes ended for Uncle Suetaro.

Lt. General Makino attempted as best possible to assemble any IJA survivors in the Mt. Canguipot area, just a couple of miles east of Villaba.

By April, 1945, only a small number of tattered, hungry and ill soldiers were believed to still be alive. In a Japanese book called Rising Sun, it was reported up to 100 Japanese soldiers were dying each day during this time from starvation and/or illness.³

If Uncle Suetaro was still alive, I passionately wonder what intense emotions were raging through him. Perhaps he thought of his mother or of his remaining siblings in America. I am here fighting to free my brothers and sister from the American concentration camps.

He must have known his young life would be ending on that island – on that hill to become another soul lost in a faraway jungle.

I can but hope his fear was overcome by tranquility.

______________________________________

The war ended four months later, on August 15, 1945.

No one walked down off Mt. Canguipot that day… in particular, my Uncle Suetaro.

An epilogue will follow and will close this series.

Part 1 is here.

Part 2 is here.

Part 3 is here.

Part 4 is here.

Part 6/Epilogue is here.

NOTES:

1. Although Aubrey “Red” Newman would survive his grievous stomach wound, he would not return to battle before war’s end. However, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his command actions and retired a Major General. He passed away in 1994 at 90 years of age.

Koji, you bring the reality of your uncle’s situation to life. Even if the key facts are not correct. I admire your passion and desire to know what happened, to find truths for your uncle and your family.

Eyewitness testimony becomes blurred with time. A desire for publicity also finds a few of those that survived battle certain leeway in presenting their version…

Reblogged this on Lest We Forget and commented:

A SOUL LOST IN A FARAWAY JUNGLE – PART 5

You managed to impress me again Koji.

Thank you again, Pierre, but I pale in comparison to your efforts to honor our past heroes.

I am just a compulsive researcher and blogger. I am truly impressed.

Ah-ha, after you so politely saying I do not make mistakes – found my very serious confusion between the 12th Cavalry Regiment and the 12th Div!!! The 11th A/B came up from behind the 7th and relieved them on 25 November.

So is my data incorrect?? I deterred from mentioning the 11th Abn as I could not locate any specific documentation the 41st Regiment clashed with them although very possible. The IJA command had broken down. Please let me know if my version is incorrect!! (ps My Android app didn’t reply to your comment. My apologies!)

[To be certain I don’t mis-type, here is an excerpt from “The Angels: A History of the 11th A/B Division”]

‘After several days of hard fighting, the 7th had reduced them and by 18 November had driven the surviving defenders into the mountains. On 20 Nov., the 11th A/B began to relieve the 184th Infantry Regiment (7th Div) in the Burauen area so it could concentrate on the Baybay area on the west coast, where it closed on the 25th.

‘The 11th was assigned a zone of action which included the Burauen area and extended thru the Cordillera in the west and almost to Abuyog in the south…

‘The 96th Div., to the right of the 11th A/B , patrolled the area from Mount Laao southeast to Mount Lobi.

‘Gen. Suzuki had 4 divisions deployed along the line. the 1st opposed the 32nd in the north; the 102nd held that portion of the central mountain ridge against which the 1st Cavalry and the 24th were attacking; the 16th was dug in and defensing the mountains in front of the 96th Div and the 11th A/B; the 26th stretched from Ormoc to Albuera and into the hills in front of the 11th’s route of attack.’

This kind of post really takes a lot of work; so well done, Koji. Thanks for this. My heart aches for Uncle Suetaro.

I suppose many have told you, but I think you should write a book.

Thank you for taking time from your busy day to visit, geeez! I have been “reading” some Japanese websites on and off but this is the first time a project has taken so long. I kind of understand now why dad said he was sent to the MIS school at the Presidio although totally fluent: he basically had to learn military terminology and procedures of the Japanese. I bit off more that I can chew…

When we lived in Paris, my German husband who spoke French, would say “the plumber’s coming and you want to know what to say? Sorry, honey, I don’t speak plumber French” …he simply didn’t have the vocab for that, so I understand your dad going to the MIS school in the Presidio ….

I say “keep biting and chewing…you have a book getting ready to be born!”

Assassination of Yamamoto?….did you really post that in all seriousness?…were all the sailors who died at Pearl before war was even declared all assassinated too?….I may offend, though not my intent, just don’t know how else to say it but I find certain ways Japanese people use to describe certain events of WW2 totally wrong. Taking out key leaders DURING the war is a viable strategy. The US used its SUPERIOR intelligence capabilities to its full extent, the killing of Yamamoto caused a great demoralazation within the ranks of the Japanese military and its people, it must have because the event was lied about to its people for a time. I have always said that “Does or did Japan truly feel justified in causing so much death and suffering across all of Asia over an oil embargo”? The Japanese government and military did not like being dependent on the US for its oil….I guess that’s what happens when a people as arrogant as the Japanese were with the superiority complex they had as well against the US. The Japanese military grossly underestimated the US will to fight…I have used reading and research material from all over the world in over 30 years as an amatuer historian, some the ways Japanese description events just leave me shaking my head. The somewhat recent wave of revisionism in Japan explains most of it, I rarely if ever see the rewriting of WW2 history anywhere else in the world…but really, the assassination of Yamamoto is totally wrong, he was killed in action during an inspection tour and was shot down in the “Betty” bomber in which he was a passenger over Bougainville…

I returned from a ten day pilgrimage to the island of Leyte to honor ALL war dead on that island so pardon the delay; internet was very elusive on that island.

While I am struggling to find in this Part 5 where I wrote this word that appears to have offended you, the phrase is not an “opinion”. The term assassination is used in many articles I have read. A number of them state FDR “ordered the assassination” and I am but reiterating it. However, please feel free to us whichever descriptive term you wish to and replace the word “assassination” with “killed” if you so please.

I said “killed” many times in my reponse…it was you who used the word assasination…not me. He was killed just any other soldier in war, but in this case the US intelligence sector got wind of his inspection tour and made a plan that in retrospect worked out beautifully…if you’re an American I suppose. I think a re-read of my reponse is in order…

Thanks again for the reply but once again – for clarification – where in this multi-part story of my uncle did I use the term “assassination”? I just want to get clarification first. I have no issue in the word killed by the way…

Right here where you say..(and I cut and paste your words)….”However, please feel free to us whichever descriptive term you wish to and replace the word “assassination” with “killed” if you so please”….I don’t feel he was assasinated, he was killed just any other soldier would have been. Just so happens Yamamoto was, at least in my opinion, the heart of soul of Japan’s war, in the way he was looked upon by Japanese military regardless of branch….

Please look at your first couple of sentences in your very first comment. It just came out of the blue in a way as I cannot find where I used that word assassination in this story of my dad and his brother… and i am not referring to my REPLY to your first comment which you copied. Please just help me out here…