“There She Goes”

In the climax of the classic Hollywood movie Sands of Iwo Jima above, the words, “There she goes,” are uttered by a fictional Marine played by Forrest Tucker.

You will soon read that those were the words apparently said in a brief conversation between Sgt. Bill Genaust and AP photographer Joe Rosenthal atop Mt. Suribachi on February 23, 1945.

And you thought Hollywood movies were all fiction…¹

_____________________________________

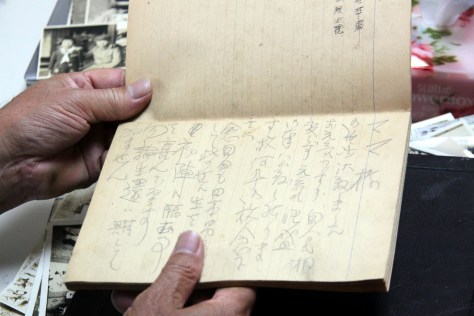

In Part 2, we left Sgt. Genaust recovering from a gun shot wound to his thigh and learning his fellow Marine and close buddy, Howard McClue, was killed soon after.

He apparently felt great loss from the death of McClue and sent a letter to his mother (above) explaining of what happened to her son that day. It is one of the few remaining letters written by Sgt. Genaust.

_______________________________________

The Flag Raising and Iconic History

According to records, Genaust recuperated from his wounds on Hawaii. According to Norm Hatch, their Colonel (who I believe to be Col. Dickson) gave Genaust the option to remain stateside due to his combat tour and wounds.

Genaust said no. Even though his Navy Cross was declined because he was not an infantryman, he rose above the disappointment and subsequently volunteered to go to Iwo Jima. At that time, no one could have anticipated the horrific savagery of battle and carnage. If you remained alive, it was by pure chance.

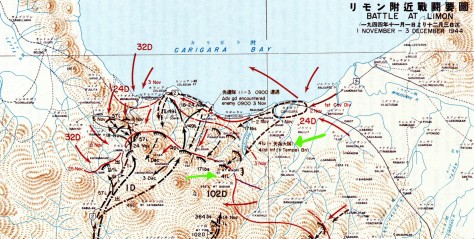

Sgt. Genaust was embedded with the 4th Marines and stormed ashore onto the talcum powder-like black sands on February 19, 1945.

When the Marines would clear an area of the enemy, they would move forward – only to have more Japanese pop out of the same caves and holes they had cleared through their vast network of underground tunnels.

In substance, there was no clear “front line”. The only front line was the ground: the Marines on the surface, the Japanese below. Instantaneous death came unseen to these young boys from every conceivable angle or location.

Think of it this way: every Marine on that stinking island was in sight of a Japanese rifle or artillery.

_______________________________________

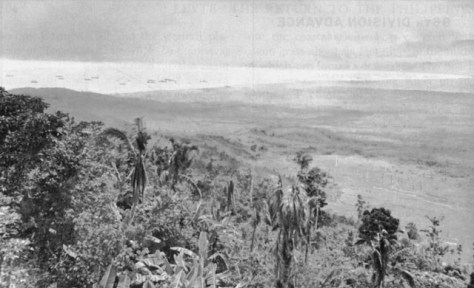

To the Top of Mt. Suribachi

Sgt. Genaust miraculously survived the furious death being hurled at him and the Marines during the first few days of the invasion. Again, his hand was steady but he was definitely “excited” as he mislabeled his sixth reel but corrected it in time. While I am unable to mark his scenes, you can see some of Genaust’s combat footage at this link immediately below. You can see his boot as he was lying prone on the sand, filming his fellow Marines invading the beachhead; in other scenes, flame throwers are captured crawling on the sand.

On February 23, 1945 (D+4), Marines were ordered to fight to the top of Mt. Suribachi. These Marines had a flag with them.

According to official USMC records, the following occurred the morning of February 23, 1945:

“Lieutenant Colonel Chandler W. Johnson, the battalion commander, decided to send a 40-man combat patrol (remnants of the 3d Platoon of Company E, and a handful of men from battalion headquarters) under command of First Lieutenant Harold G. Schrier, the Company E executive officer, to seize and occupy the crest. Sgt. Louis Lowery, a Marine photographer for Leatherneck magazine, accompanied that patrol.”²

This first flag brought ashore for this purpose was small, 54″ by 28″.

The USMC record continues:

After snapping pictures of this first flag being raised, Sgt. Lowery was sent over a crater’s edge from the blast of a Japanese grenade that had been thrown during the firefight. During the tumble, Lowery’s camera and lens were broken but the film remained secure.

Sgt. Lowery felt his mission was accomplished and started back down. In essence, he did take the first photos atop Mt. Suribachi.

During his descent, Lowery ran into Sgt. Genaust and PFC Bob Campbell (another USMC photographer)… and a civilian Associated Press photographer named Joe Rosenthal. They were climbing to the top under orders from Norm Hatch. Lowery informed them the flag had already been raised. Still, Genaust and the two other photographers thought photo ops still remained and carried on. After all, Genaust and Campbell were under orders to do so.

Prior to that – and after the first flag had been raised – PFC Rene Gagnon was carrying the second, more well known flag and walkie-talkie batteries up Mt. Suribachi on orders from Col. Johnson. He joined up with a patrol heading up the slopes led by Sgt. Michael Strank. (This group then made up five of the six Marines made famous by the photograph catching the raising of the second flag.)

_________________________________________

Per USMC records and upon reaching the summit, “Sgt. Strank took the flag from Gagnon, and gave it to Lieutenant Schrier, saying that “Colonel Johnson wants this big flag run up high so every son of a bitch on this whole cruddy island can see it.”

Sgt. Genaust took a quick movie of the first smaller flag as he approached the summit, whipped about by the wind. Then, these three cameramen men saw the first flag was about to be taken down with the more famous second flag was being readied.

Genaust, Campbell and Rosenthal hurried to their shooting positions. According to an oral interview of Joe Rosenthal, “While the photographers were taking their positions to get the shot, Genaust — the motion picture photographer — asked “Joe, I’m not in your way, am I?” Joe turned to look at Genaust, who suddenly saw the flag rising and said, ‘Hey, there she goes!'”

Genaust then filmed the entire flag raising process (below) while Rosenthal snapped that now famous image.³

__________________________________________

In a purely timing-related quirk of fate, Rosenthal’s film was processed the next day; being USMC, Campbell’s and Genaust’s were about ten days later.

Factually, Rosenthal’s 4×5 negative film was immediately sent to AP’s processing center in Guam. The staff there – after slight cropping – transmitted it back AP in the States. Rosenthal’s famous photograph hit the newspapers only 17-1/2 hours after Rosenthal snapped the picture.

No one on Iwo Jima knew about the photo nor the patriotic stir it generated at this time, less than 24 hours after it was snapped… and certainly, that it was a photo of the second flag.

Unfortunately, for Sgt. Genaust, all motion picture film successfully evacuated from the combat zone were shipped to Pearl Harbor for processing – about nine days. Where was FedEx when you needed them.

__________________________________________

Back on Iwo Jima, Hatch and Lowery began to hear scuttlebutt about a photo taken of the flag being raised on Mt. Suribachi. While some specifics differ, both Hatch and Lowery assumed the frenzy was about Lowery’s photo. Apparently, neither knew of the specifics involving the actions of Genaust and Campbell. There was a war going on. They couldn’t very well text each other.

Rosenthal also had no idea whatsoever his photo sparked nationwide optimism about the war until a short time later. His name became associated with one of the most viewed photographs of WWII.

But nobody knew of Sgt. William Homer Genaust, the Marine motion picture man who at least killed nine enemy soldiers, was wounded, then was denied the Navy Cross because he was an infantryman. And the man who took the only motion picture footage of the second flag.

And only a few knew Lowery DID take the first pictures of the first smaller US flag being raised atop Suribachi.

However, due to an errant reply from Rosenthal himself, a fury of accusations that the flag raising in the photograph was staged circulated. Indeed, since Lowery didn’t know the SECOND flag was raised while Genaust and Campbell were present fueled some anger in him. I took the picture of the flag raising! Not Rosenthal!

Ironically, it would be Sgt. Genaust’s film processed and made public a couple of weeks later that will positively prove the photo was taken as it happened and not posed.

The destiny of Sgt. Genaust and the movie will be in Part 4. Ironies will become intertwined for many, including Adelaide, his wife.

Please stay tuned.

________________________________________

NOTES:

1. The film Sands of Iwo Jima, whose invasion scene was filmed at the beaches of Camp Pendleton, a number of Marines who were in combat on Iwo Jima had cameo roles. Most significantly, Navy Corpsman PhM2C John Bradley, Corporal Ira Hayes and Pfc. Rene Gagnon were in the last scenes as well in the movie clip above. There were six flag raisers; of the three, only Bradley, Hayes and Gagnon survived the battle. The other three – Sgt. Mike Strank (26), Cpl. Harlon Block (21) and Pfc. Franklin Sousley (19) – were killed in action on Iwo Jima.

2. Lt. Schrier has a cameo role in the same movie, Sands of Iwo Jima.

3. The footage here is reportedly colorized meaning Sgt. Genaust’s original footage is in B&W. However, I understand that all USMC 16mm motion picture footage was color (specifically, Kodachrome).

The Nissho Maru is listed in this WWII era Division of Naval Intelligence report.

The Nissho Maru is listed in this WWII era Division of Naval Intelligence report.