My LA cousins held a third anniversary Buddhist memorial service for our Aunt Shiz today (August 15, 2015), ironically the day 70 years ago that Emperor Hirohito broadcast to his citizens that Japan was surrendering.

I was reporting in person to my LA cousins of our pilgrimage to Leyte as well. Bessie, my cousin and Aunt Shiz’s only daughter, shared with me something about her mom that echoed of the reason for the pilgrimage.

She told me Aunt Shiz used to watch “Victory at Sea” on the TV for years. “Mom, why do you always watch it?” she asked.

Aunt Shiz replied, “Because I may get a glimpse of Sue-boh…”

Think of the irony. Aunt Shiz was watching a US Navy-backed documentary series of our WWII victory over Japan… in hopes of seeing her youngest brother captured on some US movie footage.

Indeed… One war. Two countries. One family.

_________________________________________________

Day 3 – Evening / Break Neck Ridge

After the memorial service during which I read my letters, we went up a winding road. The road had a few stetches where it had given way and slid down the side of the hill. Sure kept my attention but our drivers were excellent.

We then made a stop near the crest of a hill: we were at the actual Break Neck Ridge battle site.¹

There was a flight of uneven concrete and dirt stairs to the top; a hand rail was on one side only yet our firmly driven Masako-san unhesitatingly took on the challenge and strongly made the climb.

There was a flight of uneven concrete and dirt stairs to the top; a hand rail was on one side only yet our firmly driven Masako-san unhesitatingly took on the challenge and strongly made the climb.

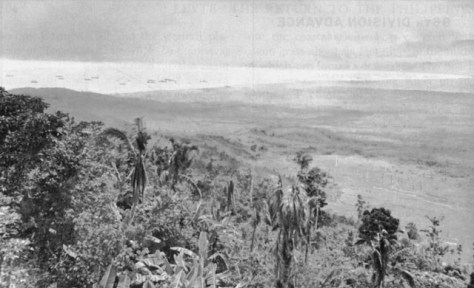

Once on top of the hill, you could not help but notice you were surrounded by the sounds of insects hidden in the tall grass and birds singing as the sun once again played hide and seek. Standing at the crest gave you a sweeping view of the terrain. Indeed, the Japanese defenders had the advantage, costing many American casualties.

My July 2015 photo from about a similar location:

According to Mr. Ota and US battle reports, the US would continually shell the hillsides to soften up Japanese defensive positions. However, when the shelling or bombing would begin, the Japanese soldiers would temporarily abandon their weapons and via established and well camouflaged foot trails or tunnels, run to the backside of the hill. There, they were shielded against the shelling. Once the barrage or bombing would lift, they would scamper back to their defensive positions and await the US soldiers advancing up the hill.

There was also another short climb off to the right. The vegetation was thicker, chest high in some places and the grass’ sharp edges irritated your exposed legs as you walked through. To give you a small sense of the surroundings, Mr. Ota is speaking of the defensive advantage and Mr. Kagimoto is coming back down the smaller hill, flanked by the vegetation. The height of the grasses can be easily judged; they’re having a slight drought, by the way:

While American memorials were absent, there were a number of Japanese ones:

We said some prayers for those who are still on this island and made our way back down.

________________________________________________

Ormoc City and Port

We then headed south nearly the entire length of Leyte, down the two lane Pan-Philippine Highway towards Ormoc City and its dock. Uncle Suetaro disembarked from his Japanese troop transport on this very dock on October 26, 1944.

The dock reaches into Ormoc Bay, the sight of tremendous life and death struggles between US airpower and Japanese shipping. Although the Allies commanded the air, MacArthur was slow to catch on that the Japanese were unloading thousands of reinforcements (including Uncle Suetaro) and supplies. Once MacArthur caught on, it was a certain violent end to a number of troops still at sea. Tons of critical supplies were also sent to the bottom, thereby ensuring the defeat of Japanese troops on Leyte.²

Two palm tree stumps across the street from the hotel are left from the war; dozens of bullet holes pepper the two trunks. The yellow steel fencing can also be seen in the lower right of my photo above to help give a sense of where these tree trunks are.

After all took very quick and much needed showers, we enjoyed an informal dinner outdoors, ordering local grilled items from a mother-daughter food stand. It was still quite warm and therefore steamy but a jovial mood took over after a long day. I didn’t quite know what everything was but my cousins – who had very little food for years – happily dined on whatever was brought out.

After all took very quick and much needed showers, we enjoyed an informal dinner outdoors, ordering local grilled items from a mother-daughter food stand. It was still quite warm and therefore steamy but a jovial mood took over after a long day. I didn’t quite know what everything was but my cousins – who had very little food for years – happily dined on whatever was brought out.

After talking about the events of the day and on our way back to the hotel, Carmela encouraged all five ladies to experience a group ride on a “tricycle”, which is a 125cc motorcycle with an ungainly but colorfully decorated side car. The only time I’ve seen girls more giddy was when I took my Little Cake Boss and friends mall shopping – twice.

Remember how lots of college kids would pile into on phone booth? Well, those college kids would have been proud. All five ladies piled in!

Remember how lots of college kids would pile into on phone booth? Well, those college kids would have been proud. All five ladies piled in!

While we all had a wonderful, relaxing evening alongside Ormoc Bay, I am sure each realized that both Uncle Suetaro and Lt. Nakamura had begun their march to their deaths from these very grounds on October 26, 1944.

The final memorial services for our graveless souls in Part 7.

__________________________________________

Other chapters are here for ease of locating earlier posts in this series:

A Soul Lost From WWII Comes Home – Part 1

A Soul Lost From WWII Comes Home – Part 2

A Soul Lost From WWII Comes Home – Part 3

A Soul Lost From WWII Comes Home – Part 4

A Soul Lost From WWII Comes Home – Part 5

A Soul Lost From WWII Comes Home – Part 7

A Soul Lost from WWII Comes Home – Part 8

A Soul Lost From WWII Comes Home – Epilogue

NOTES:

- For those interested, this link will take you to an actual WWII “Military Intelligence Bulletin”. Dated April 1945, there is a section of the battle including descriptions of the tactics and dangers of fighting on that series of ridges. Interestingly, the publication was issued by G-2, Military Intelligence. My dad was part of G-2 albeit postwar. Please click here.

- The critical Gulf of Leyte sea battle took place between October 23 and October 26, 1944, when Uncle Suetaro was en route to Ormoc Bay. Through critical US ship identification errors by the then superior Imperial Japanese Navy force (including the battleship Yamato), they engaged Taffy 3, a small defensive US naval force. Although the battle had been won tactically by the Japanese, they inexplicably turned back. A CGI recap is here on youtube.

The Nissho Maru is listed in this WWII era Division of Naval Intelligence report.

The Nissho Maru is listed in this WWII era Division of Naval Intelligence report.