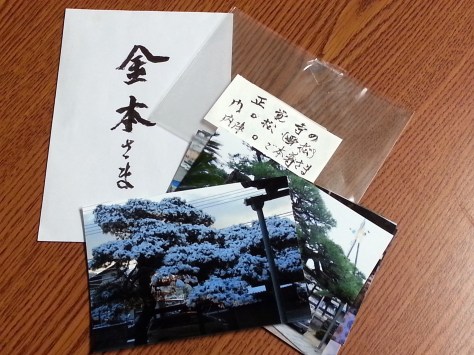

正覚寺。

Catchy title?

In the past several years, as his dementia progresses, Dad is repeating many times how he broke his elbow as a young boy… “Many times” like as in every four minutes. No…every two.

I thought, “He doesn’t remember he ate like a horse ten minutes ago… How can he remember something that happened 80+ years ago?”

Well, I just HAD to find out about his story… and I did.

_______________________________

The story (which never varies) is/was he was playing “oninga”, or tag, with the neighborhood kids. “There was nothing else to do then,” he would tell me. They would end up in the yard of 正覚寺 – pronounced “Shoukakuji” – the Buddhist temple which is a hop, skip and a jump from his home. No wonder he excelled in the triple jump at Nichu.

You can see a tiled roof on the tallest structure to the right of him. That is 正覚寺.

For those who like visuals:

He would tell me (over and over) that while playing tag, “…I tried to get away so I jumped on this big round stone then leaped up to a branch on big a pine tree in front of 正覚寺.”

Now that I know he did the broad jump at Nichu, I thought this jumping thing was therefore plausible. (Did I mention I’m a writer for “Mythbusters”?)

“Trouble is, I jumped too far so my hands couldn’t grab onto the branch. I slipped off the branch then broke my elbow when I hit the ground”.

OK. So now, after “An Atomic Spark From a 1937 Yearbook“, I also know he excelled in the triple jump at Nichu. Plausible. (See… More proof I am a writer for “Mythbusters”.)

To this day, he cannot completely straighten out his right arm. It’s crooked. He now tells this story to my youngest kids, Jack and Brooke… Every four minutes.

______________________________________

On September 7, 2012, I had to know. Off to 正覚時… But unlike my agile father of the 1920’s, I was walking very gingerly. There were four humongous blisters on my toes from walking in Japan and (from being tricked into) climbing Mt. Misen on Miyajima.

Indeed, there was a Japanese pine tree, or “matsu”. A huge one. You couldn’t miss it as you walk through the “mon”, or gate. It was so huge, the temple had steel braces installed to help hold these majestic branches up.

Off the to right, was the base of the tree. A puny trunk in relation to the Goliath branches… It was hard to believe at first this small trunk was the heart for this proud tree.

Then… at the base… was a large round stone. Could it possibly be? Plausible as we don’t know how long the stone was there… Am I tough?

But where’s the branch my father jumped for? Myth: Busted!… or so I thought.

Then we saw it. Above my son Takeshi in the picture. The base of a broken branch. It was at the right height! OK… Myth: Plausible.

But conclusive proof was just beyond reach. There was no evidence as to age of the tree or how long the stone was there…

Then, as if Aunt Shiz summoned him, the reverend of 正覚寺 came out…with his wife. He was about 90 years old. Almost as old as my dad but he still had his wits about him. Thank goodness.

He told us he didn’t know my father personally…but that he played with Suetaro and Mieko, Dad’s youngest brother and sister! He knew Suetaro well, he said. He listened to Suetaro blow on his flute from the house in the evenings.

My Japanese wasn’t good enough so Masako stepped in… She explained to the elderly reverend how my dad (her uncle) had jumped from a large round stone at the base of a pine tree here 80+ years ago and broke his elbow.

Unbelievably, the reverend said with pride, “The pine tree is about 400 years old…and that stone has been there for as long as I can remember. It hasn’t been moved, either.”

Then the wife said that a number of years ago, the branch had broken off but it was very long. Then after it broke off, “…a swarm of bees made a home inside. We had to seal the crack unfortunately,” to account for the mortar on the branch.

Was his story a myth? Busted? Plausible? Confirmed?

Myth: Confirmed.

Dad wasn’t imagining ANYTHING. His memory is intact from that time.

Mission accomplished.

_____________________________________

But to end this fun story, we had my Aunt Shiz’s interment the next morning.

The reverend’s son was the officiant. Glorious. The circle of generations continues. And he brought along one more piece of treasure to the interment:

A photo of the majestic Japanese pine tree covered in snow.

_______________________________________

There are souls in this tree, too.

Oh… I was kidding about Mythbusters.